PROPOSED HABITAT PROTECTION CLOSURE

FORT FUNSTON

GOLDEN GATE NATIONAL RECREATION AREA

NATIONAL PARK

SERVICE

GOLDEN GATE NATIONAL RECREATION AREA

CORRECTION TO NOTICE OF PROPOSED YEAR-ROUND CLOSURE AT

FORT FUNSTON

AND REQUEST FOR COMMENTS

CORRECTION: Public comments on this notice must be received by September 18, 2000.

(note: later the deadline was extended to Oct. 6, 2000).

Dated: July 17, 2000.

Brian O'Neill

Superintendent, GGNRA

NATIONAL

PARK SERVICE

GOLDEN GATE NATIONAL RECREATION AREA

NOTICE

OF PROPOSED YEAR-ROUND CLOSURE AT FORT FUNSTON

AND REQUEST

FOR COMMENTS

COMMENTS:

Public comments will be accepted for a period of 60 calendar days from the date

of this notice. Therefore, public comments on this notice must be received by

September 12, 2000. Public comments should be submitted to NPS as early as possible

in order to assure their maximum consideration. Comments will be considered

and this proposal may be modified accordingly, and the final decision of the

National Park Service will be published in the Federal Register.

If individuals submitting

comments request that their name and/or address be withheld from public disclosure,

it will be honored to the extent allowable by law. Such requests must be stated

prominently at the beginning of the comments. There also may be circumstances

wherein the NPS will withhold a respondent's identity as allowable by law. As

always, NPS will make available for public inspection all submissions from organizations

or businesses and from persons identifying themselves as representatives or

officials of organizations and businesses; and, anonymous comments may not be

considered.

SEND COMMENTS

TO: Superintendent, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Bay and Franklin

Streets, Building 201, Ft. Mason, San Francisco, 94123.

FURTHER INFORMATION:

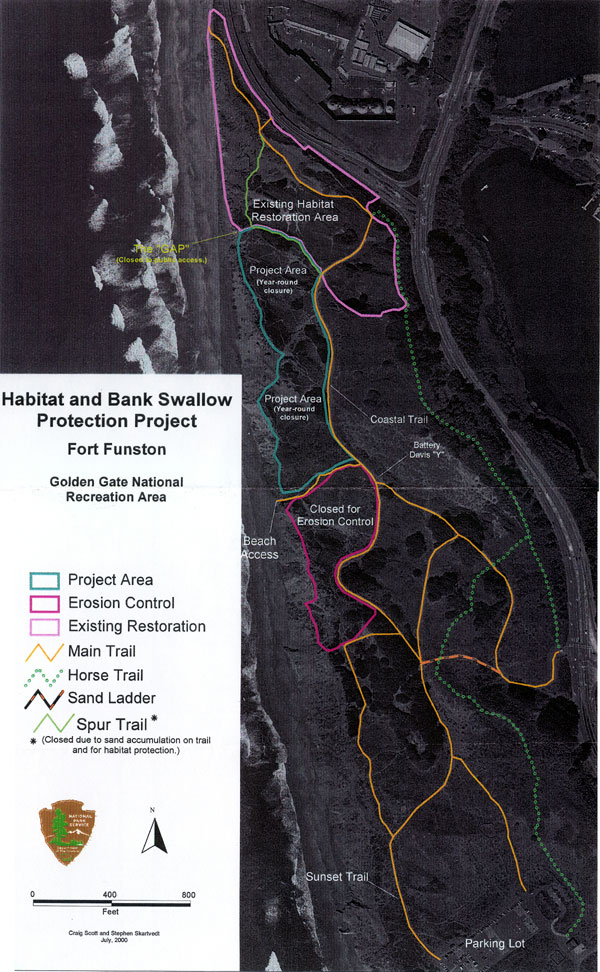

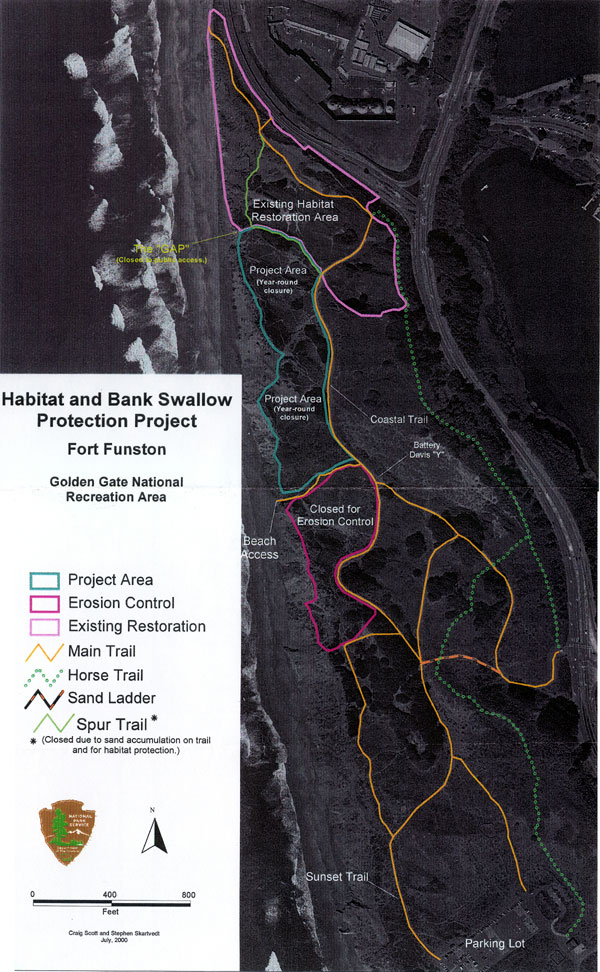

Detailed information concerning this proposal, including a map

depicting the closure

area and open park trails, is available at the following locations:

CONTACT: For further

information, contact Scalla Sheen, Office of Public Affairs, GGNRA at 415

561-4730.

Dated - July

14, 2000.

Brian ONeill

Superintendent, GGNRA

As part of the resource

protection mission of the National Park Service (NPS), approximately 12-acres

of Fort Funston is being closed year-round to off-trail recreational use by

the public. This action will protect habitat for a nesting colony of California

state-threatened bank swallows (Riparia riparia), a migratory bird species once

more common along the California coast that has declined significantly due to

habitat conversion and increased recreational use. This closure is also necessary

to enhance significant native plant communities, improve public safety, and

reduce human-induced impacts to the coastal bluffs and dunes, a significant

geological feature.

Part of the Golden Gate

National Recreation Area (GGNRA), Fort Funston spans approximately 230 acres

along the coastal region of the northern San Francisco peninsula. It is located

south of Ocean Beach and north of Pacifica, and is flanked to the east by both

John Muir Drive and Skyline Boulevard, and to the west by the Pacific Ocean.

The proposed year-round closure is located within the northern region of Fort

Funston and is depicted on the attached map as "Project Area (Year-round closure)."

It is defined to the west by the edge of the coastal bluffs; to the east by

the Coastal Trail; to the north by protective fencing installed in the early

1990s for habitat protection; and to the south by a pre-existing "beach access"

trail west of the Battery Davis "Y". There is currently fencing erected around

the eastern and northern perimeters of the proposed year-round closure area.

Additional fencing will be erected along the southern boundary, parallel to

the "beach access" trail (see map). This fencing will be peeler post and wire

mesh design, consistent with the existing fencing that was erected in February-April

2000.

The entire 12-acre project

area will be closed year-round to visitor access. There is a portion of one

designated trail located within the footprint of this closure. This trail, known

as the "Spur trail" (see map), will be closed to visitor use because southern

sections of this trail have become unusable due to increased sand deposition

on the trail surface. This has compounded the establishment and use of unauthorized

"social" trails in the northern section of the project area. Visitor use of

and access to all "social" trails including "the Gap" (see map) within the project

footprint will be prohibited by this closure.

II.

HISTORY - Fort Funston

Prior to Fort Funston's

purchase by the Army, the site supported a diversity of native dune vegetation

communities. During the 1930s however, the Army built an extensive system of

coastal defense batteries, drastically altering the dune topography east of

the bluffs and, in the process, destroying much of the native plant communities

that inhabited the dunes. Following construction, the Army planted iceplant

(Carpobrotus edulis) in an attempt

to stabilize the open sand around the batteries.

By the mid-1960s, extensive

areas of Fort Funston were covered with invasive exotic plants such as iceplant

and acacia. Some years after Fort Funston was closed as a military base, it

was transferred to the National Park Service in 1972 to become part of the GGNRA.

As a unit in the national park system, Fort Funston today is used extensively

by beachcombers, walkers, hang gliders, paragliders and horseback riders, and

other recreational users. Approximately three-quarters of a million visitors

enjoy Fort Funston annually.

III.

CLOSURE JUSTIFICATION

This closure is necessary

to protect habitat for the California State-threatened bank swallows (Riparia

riparia), enhance significant native plant communities, improve public safety

and reduce human-induced impacts to the coastal bluffs and dunes, a significant

geological feature. The National Park Service has authority to effect closures

for these purposes pursuant to Section 1.5 of Title 36 of the Code of Federal

Regulations. Specifically, Section 1.5 authorizes the Superintendent to effect

closures and public use limits within a national park units (sic)

when necessary for the maintenance of public health and safety, protection of

environmental or scenic values, protection of natural or cultural resources,

aid to scientific research, implementation of management responsibilities, equitable

allocation and use of facilities, or the avoidance of conflict among visitor

use activities. As discussed in detail below, the proposed closure at

A. The Threatened Bank

Swallow

One of the many unique features of Fort Funston is that it supports one of the

last two remaining coastal

cliff-dwelling colonies in California for the bank swallow (Riparia riparia).

Once more abundant throughout

the state, their numbers have declined so dramatically that in 1989 the State

of California listed the bank

swallow as threatened under the California Endangered Species Act. The bank

swallow is also a protected

species under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and for nearly a century, the bank

swallows have returned

to Fort Funston each March or April to nest and rear their young along the steep

bluff faces. NPS regulations,

policies and guidelines mandate the protection and preservation of this unique

species and its habitat.

Its preferred habitat --

sheer sandy cliffs or banks -- has been altered throughout its range by development,

eliminated by river channel stabilization, and disrupted by increased recreational

pressures. The Fort Funston colony is particularly unique in that it is one

of only two remaining colonies in coastal bluffs in California, the other being

at Aņo Nuevo State Park in San Mateo County. Bank swallow habitat at Aņo Nuevo

remains closed to visitor access.

Mortality of bank swallows

results from a number of causes including disease, parasites and predation.

Destruction of nest sites, including collapsed burrows due to natural or human-caused

sloughing of banks, appears to be the most significant direct cause of mortality

(Recovery Plan, Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia), State of California Department

of Fish and Game 1992). The Recovery Plan recommends a habitat preservation

strategy through protection of lands known to support active colonies or with

suitable habitat features for future colony establishment. It also acknowledges

that isolated colonies, like Fort Funston, are at particularly high risk of

extinction or severe population decline. Additionally, the State of California

Historic and Current Status of the Bank Swallow in California report (1988)

recommended that nesting colonies be protected from harassment and human disturbance.

The Fort Funston colony

has been recorded since at least 1905. Records indicate that the colony fluctuated

in size and location overtime. A 1961 study of the Fort Funston colony documented

a total of 84 burrows in 1954, 114 in 1955, 157 in 1956, and 196 in 1960. GGNRA

staff counted at least 229 burrows in 1982 and more than 550 in 1989. In 1987

the California Department of Fish and Game documented 417 burrows at Fort Funston.

Approximately 40 to 60 percent of burrows are actively used for nesting in a

given year.

Between 1992 and 1995,

NPS implemented other protection and restoration measures for the Fort Funston

colony, including a year-round closure of approximately 23-acres in the northern

most portion of Fort Funston to off-trail recreational use. The current proposed

closure area lies directly south of this previous closure area. From 1954-56

and from 1989-97, the colony was located along the bluffs within the footprint

of this previous closure. However the colony shifted during 1959 and 1960, and

again since 1998, such that birds are now nesting within the current proposed

closure area.

In 1993,GGNRA established

an annual monitoring program to track the abundance and distribution of bank

swallows at Fort Funston. Trained personnel conduct weekly surveys during nesting

season (from mid-April through early August). From 1993 to 1996, burrow numbers

were over 500 each year. The number declined dramatically to only 140 in 1998

and 148 in 1999 when the colony shifted to the current proposed closure area

(then unprotected). This event coincided with the storms during the winter of

1997 that caused significant cliff retreat and slumping. In an attempt to protect

the colony from recreational disturbance of nesting habitat, protective fencing

was installed along the bluff top in 1998 with interpretive signs to encourage

visitors to reduce impacts on the nesting colony. These efforts proved unsuccessful

in preventing recreational disturbance to the colony. NPS observed increased

erosion due to visitor use adjacent to the fenceline. Moreover, the rate of

natural bluff erosion, approximately one foot per year, and the constant deposition

and erosion of sand material caused the fence to collapse and fail within just

a few months. Fence posts near the bluff face also provided advantages to swallow

predators that perch on the posts with a view to the swallow nests.

A wide array of disturbances to

the swallows at Fort Funston have been observed and recorded during monitoring,

and/or photo-documented. While bank swallows are known to be quite tolerant

to some disturbance, few colonies are subjected to the intense recreational

pressure at Fort Funston. Documented disturbance events at Fort Funston include:

cliff-climbing by people and dogs; rescue operations of people and dogs stuck

on the cliff face; people and dogs on the bluff edge or in close proximity to

active burrows; graffiti carving in the cliff face; aircraft and hang-glider

over-flights; and discharge of fireworks within the colony. The potential impacts

from such disturbances include: interruption of normal breeding activity, such

as feeding of young; crushing of burrows near the top of the cliff face (nests

can be located within a foot of the bluff top); casting shadows that may be

perceived as predators; accelerating human-caused bluff erosion; and active

sloughing and land-slides that may block or crush burrows and the young inside.

The NPS has determined

that the designated trails (see map) at Fort Funston provide adequate access

to the park area and that continued use of unauthorized "social" trails within

the project footprint has adverse impacts on park resources, including the bank

swallow.

The institution of the

proposed 12-acre closure area, coupled with increased interpretive signs and

strategically located protective barriers at the base of the bluffs will protect

the bank swallow colony by preventing most of these disturbances. There will

be no visitor access to the bluff edges above the nesting sites, thus preventing

falls and rescues on the cliff face, as well as human-induced erosion, crushing

of burrows, and casting of shadows. Visitor access up the bluffs from the beach

into the closure area will be prohibited, thus avoiding human-induced erosion

of the bluffs and habitat disturbance.

B. Geology

and Erosion

The bluffs at Fort

Funston provide one of the best continuous exposures of the last 2 million years

or more of geologic history

in California, covering the late Pliocene and Pleistocene eras. This exposure

of the Merced Formation

is unique within both the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and the region.

It is a fragile, nonrenewable

geologic resource. NPS regulations, policies and guidelines mandate

preservation of such resources

by preventing forces (other than natural erosion) that accelerate the loss

or obscure the natural features

of this resource.

Recreational use along

the bluff top contributes to a different type of erosion than the natural processes

of undercutting and slumping. Concentrated wave energy at the base of the bluffs

naturally leads to bluff retreat typically occurring during winter season when

the bank swallows that nest in the vertical bluff faces are absent. Natural

weathering and erosion from rainfall runoff and wind contribute to loss of the

bluff face. During spring and summer, when park users clamber around the bluff

top, erosion occurs from the top to the bottom, compromising the bluff face.

Slumps caused by heavy visitor traffic along the bluff top can induce sand slippage

and may even wipe out burrows during nesting season. Geologist Clyde Warhaftig

described areas of this unique sand bluff formation as crushable with the fingers

and indicated, in 1989, that people climbing the cliff faces would induce additional

erosion and that such activity should be prevented.

Additionally, erosion has

been both documented and observed throughout the inland topography of the closure

area. Continued heavy visitor use in this inland dune bluff area and associated

human-caused erosion along unauthorized "social" trails is likely to further

shorten the lifespan of the bluffs, an additional threat to the long-term existence

and sustainability of suitable habitat for the Fort Funston bank swallow colony.

The proposed closure will

preserve the unique bluffs by preventing destructive human activity around the

bluff tops and permitting the inland dune features to recover from human-induced

erosion.

C. Conservation

and Restoration of Dune Habitats

Fort

Funston is the largest of several significant remnants of the San Francisco

dune complex -- once the

4th

largest dune system in the state that covered more than 36 square kilometers

of San Francisco. More

than 95% of the original dune system has been drastically altered by urbanization

and development

Removing iceplant and other

invasive exotic plant species is one of the most important strategies for restoring

dunes. At Fort Funston, iceplant dominates more than 65% of the dunes. The California

Exotic Pest Plant Council rates iceplant on its "A" list, which includes those

species that are the Most Invasive and Damaging Wildland Pest Plants. "Even

when [natural] processes are protected, the very nature of dunes, which are

prone to disturbance and characterized by openings in the vegetation, renders

them constantly susceptible to the invasion of non-native species-especially

in urban settings. For these reasons, restoration is an essential component

of dune conservation in northern California." (Pickart and Sawyer 1998).

Dense iceplant cover also

affects the diversity and abundance of native insects and other wildlife. In

a study of sanddwelling arthropod assemblages at Fort Funston, Morgan and DahIsten

compared diversity between iceplantdominated plots and areas where native plants

had been restored. They found that "overall arthropod abundance and diversity

are significantly reduced in iceplant dominated areas compared to nearby restored

areas

....

If plant invasion and native plant restoration dramatically affect arthropod

communities as our data indicate, they may also have wider reaching effects,

on the dune community as a whole. This research demonstrates the importance

of native plant restoration for sand-dwelling arthropod communities" (Morgan

and Dahlsten 1999).

In a report last year, the Director of the National Park Service wrote that

"it is undisputed that without decisive, coordinated action the natural resources

found within the National Park System will disappear as a result of invasive

species spread" (Draft NPS Director's Natural Resource Initiative - Exotic Species

Section, 1999). Emphasis on the need to address invasive exotic species issues

and control was further stressed through

Executive Order 13112 on Invasive Species signed February 3, 1999. "Sec.

2 (a) each Federal Agency whose actions may affect the status of invasive species

shall

...

(2) (i) prevent the introduction of invasive species; (ii) detect and respond

rapidly to and control populations of such species in a cost-effective and environmentally

sound manner; (iii) monitor invasive species populations accurately and reliably;

(iv) provide for the restoration of native species and habitat conditions in

ecosystems that are invaded

... (vi)

promote public education on invasive species and means to address them.."

Increasingly heavy off-trail

use has contributed to the deterioration of native dune communities at Fort

Funston. Native dune vegetation is adapted to a harsh environment characterized

by abrading winds, desiccating soils, low nutrient conditions, and salt spray,

but it is not adapted to heavy foot traffic. Only a few species (a few annual

plants, coyote bush

(Baccharis

pilularis)) are able to survive repeated trampling. NPS has determined that

the designated trails (see map) at Fort Funston provide adequate access to the

park areas, including ingress and egress to the beach, and that continued use

of unauthorized "social" trails within the project footprint has adverse impacts

on the park resources, including the native dune vegetation.

Increasingly, heavy off-leash

dog use has also led to the deterioration of native dune communities. When on

a leash, the effects of dogs on vegetation and other resources is focused along

a trail corridor already disturbed by other recreational activities. When dogs

are off-leash, their impacts are spread throughout a larger area. Trampling

of vegetation caused by roaming dogs weakens the vegetation in the same manner

as trampling by humans; in areas where off-leash dog use is concentrated, such

intensive trampling destroys all vegetation, even the extremely tolerant iceplant.

Also, the dune soils at Fort Funston are naturally low in nutrients. Deposition

of nutrients via dog urine and feces may alter the nutrient balance in places

and contribute to the local dominance of invasive non-native annual grasses

that prosper in high-nitrogen soils (e.g.,

farmers foxtail (Hordeum sp.), wild oats

(Avena sp.), ripgut brome (Bromus diandrus)). Other adverse

impacts documented and observed by park staff include off-leash dogs digging

and uprooting vegetation.

D. Public

Safety

Cliff rescues in the Fort Funston area are a serious threat to public safety

and have a direct impact on the bank swallow colony. Numerous rescues of dogs

and people every year are necessary as a result of falls and/or when those climbing

the unstable cliffs find themselves unable to safely move up or down. These

rescues can cause injuries to both the rescued and the rescuers, compromising

public safety and natural resources at Fort Funston. Additionally, technical

rescues, such as cliff rescues at Fort Funston, tie up a large number of park

personnel and equipment, leaving major portions of GGNRA unprotected. NPS must

take all measures to reduce these preventable emergency rescues to ensure that

the limited rescue personnel are available for emergencies throughout the park.

Visitor use at Fort Funston

has increased significantly over the past five years, with annual visitation

now reaching more than

750,000. Fort Funston has also become the focal point for cliff rescues in San

Francisco. An updated review

of law enforcement case incident reports indicates the following statistics.

Prior to 1998 there was

an average of just three cliff rescues per year involving dogs and/or persons

stranded on the cliffs

at Fort Funston. In 1998 the number of cliff rescues at Fort Funston jumped

to 25. In 1999, park rangers

performed 16 cliff rescues at Fort Funston.

By contrast, there were

a total of 11 cliff rescues in 1998 along the remaining nine miles of San Francisco

shoreline from Fort Point to the Cliff House. In 1999, there were four rescues

along this stretch of coastline which includes a myriad of hazardous cliffs,

and supports an annual visitation of approximately 2 million visitors. There

were however, no dog rescues within this region during the past two years, largely

because the leash laws are enforced, and because several especially hazardous

areas are closed and fenced off for public safety.

There are several factors

that have contributed to the increase in cliff rescues at Fort Funston. First,

the severe winter storms in 1997/98 significantly eroded the bluffs, creating

near-vertical cliff faces adjacent to and below some unauthorized "social" trails

along the bluffs and causing more falls over the cliffs. Second, the increasing

numbers of off-leash dog walkers at Fort Funston have resulted in many dog rescues,

as well as three injured dogs and one dog death from failing off the cliffs

at Fort Funston in just the past two years.

The National Park Service

has determined that the designated trails (see map) at Fort Funston provide

adequate access to the park areas, including ingress and egress to the beach,

and that continued use of unauthorized "social" trails within the project footprint

is a safety hazard for visitors and park rescue personnel.

The proposed closure will

protect visitors, their pets, and the rescue personnel from unnecessary injury

and will reduce the costly and time-consuming cliff rescues at Fort Funston

by preventing access to dangerous cliff areas, and unauthorized use of "social"

trails.

IV.

PREVIOUS PROTECTION EFFORTS

GGNRA began pro-active

management of the bank swallow colony in 1990, following ranger observations

of destructive visitor activities including climbing the cliffs to access nests,

carving of graffiti in the soft sandstone, and harassment of birds with rocks

and fireworks.

Implementation of an approved

bank swallow protection and management strategy began in the fall of 1991, and

continued for the next five years. This management strategy included: (1) closing

and protecting 23 acres of the bluff tops by installing barrier fencing and

removing exotic vegetation above the bank swallow colony; (2) requiring all

dogs to be on-leash and all users to be on an authorized, existing trails (sic)

when travelling through the closed area -- all off-trail use was prohibited;

and (3) creating a 50-foot seasonal closure at the base of the cliffs where

the swallows nest to create a buffer area during breeding season, further protecting

bank swallows from human disturbance. GGNRA hang-gliding permit conditions also

prohibit flight over the nesting area during breeding season to reduce colony

disturbance.

Between

1992 and 1995, over 35,000 native plants were propagated at the Fort Funston

nursery and outplanted in the newly restored dunes within the 23-acre closure.

This was accomplished through thousands of hours of community volunteer support.

This restoration area now supports thriving native coastal dune habitat and

several locally-rare native wildlife species including California quail (Callipepla

califomica), burrowing owls (Athene cunicularia) and brush rabbits

(Sylvilagus

bachmani)

and a diversity of other native wildlife. California quail now survive in

only a few isolated patches of habitat within San Francisco and is (sic)

the subject of a "Save the Quail" campaign by the Golden Gate Audubon Society.

Burrowing owls are designated as a state species of concern. California quail

are considered a National Audubon Society WatchList species in California because

of declining populations. Brush rabbits are not known to occur in any other

San Francisco location within GGNRA.

V.

PROJECT GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

The National Park Service

is proposing to extend the existing 23-acre protection area based upon the following

factors:

2. Increase biological diversity by restoring native coastal dune scrub habitat

3. Increase public safety

4. Protect the geologic

resources including bluff top and interior dunes from accelerated human-induced

erosion.

An interdisciplinary team

of GGNRA staff determined the size and footprint of the proposed closure and

the design of the protective fence. In considering alternatives, the team evaluated

whether the project goals and objectives were met, the ability to achieve compliance

within the closure, the long-term maintenance required, the feasibility and

costs of construction, and the impacts to recreational uses.

To achieve the goals and

objectives listed above, the proposed closure was initially selected by NPS

in 1999. However, in January 2000, NPS began implementation of a less restrictive

closure that was developed after a series of NPS meetings with representatives

of the dog walking community. The less restrictive closure entailed reducing

the project footprint and opening over half of the area to visitor access when

bank swallows were not present at Fort Funston. Since that time, extensive litigation

regarding the closure has resulted in the development of an exhaustive record

of evidence that, when reevaluated, supports the currently proposed permanent

closure. NPS has determined that the less restrictive closure is inadequate

to meet the mandate of the National Park Service, in light of significant adverse

impacts on natural resources, threats to public safety, infeasibility of fence

maintenance and difficulty of closure enforcement.

NPS has determined that

the currently proposed permanent closure, as depicted on the attached map, is

necessary to achieve the goals and objectives outlined above, and is the least

restrictive means to protect the resources and preserve public safety at Fort

Funston and elsewhere within GGNRA.

VI. PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT

Because of a May 16, 2000,

Federal District Court ordered preliminary injunction against the NPS, which

disallows the closure until such time as appropriate public notice and opportunity

for comment was provided, NPS provided notice of the proposed closure in the

Federal Register on July 18, 2000, and invites comments from the public on this

proposed year-round closure.

Public comments will be

accepted for a period of 60 calendar days from the date of the notice. Therefore,

public comments on this notice must be received by September 18, 2000. Comments

will be considered and this proposal may be modified accordingly, and the final

decision of the NPS will be published in the Federal Register.

If individuals submitting

comments request that their name and/or address be withheld from public disclosure,

it will be honored to the extent allowable by law. Such requests must be stated

prominently at the beginning of the comments. There also may be circumstances

wherein the NPS will withhold a respondent's identity as allowable by law. As

always, NPS will make available for public inspection all submissions from organizations

or businesses and from persons identifying themselves as representatives or

officials of organizations and businesses; and, anonymous comments may not be

considered.

GGNRA ADVISORY COMMISSION

MEETING: Comments will also be received at the August 29, 2000, GGNRA Advisory

Commission meeting to be held at 7:30 p.m. at park headquarters, building 201,

Upper Fort Mason at the intersection of Bay and Franklin Streets, San Francisco,

California.

Albert,

M.E. 1995. Morphological variation and habitat associations within the Carpobrotus

species complex in coastal California. Masters thesis, University of California

at Berkeley.

Albert, Marc. Natural Resources Specialist, National Park Service. (personal

communication 1998-2000).

Bank swallow monitoring data for Fort Funston, Golden Gate National Recreation

Area. 1993-1999. National Park Service. Unpub data.

Bonasera, H., and Farrell, S. D., 2000. On-site public education data collected

during the project coordination for the bank swallow protection and habitat

restoration efforts at Fort Funston. Unpub.

Cannon, Joe. Natural Resources Specialist, National Park Service. (personal

communication 1998-2000).

Collman, Dan. Roads and Trails Foreman. National Park.Service. (personal communication

2000).

Clifton, H. Edward, and Ralph E. Hunter. 1999. Depositional and other features

of the Merced Formation in sea cliff exposures south of San Francisco, California.

In Geologic

Field Trips in Northern California. Edited

by David L. Wagner and Stephan A. Graham. Sacramento: California Department

of Conservation, Division of Mines and Geology.

Cutler. 1961. A Bank Swallow Colony on an Eroded Sea Cliff. unpub.

D'Antonio, C. M. 1993. Mechanisms controlling invasion of coastal plant communities

by the alien succulent

Carpobrotus edulis. Ecology 74 (1): 83-95.

D'Antonio, C.M., and Mahall, B. 1991. Root profiles and competition between

the invasive exotic perennial

Carpobrotus edulis and two native shrub species in California coastal

scrub. American Journal of Botany 78:885-894.

Freer, L. 1977. Colony structure and function in the bank swallow

(Riparia Riparia).

Garrison, Barry. 1988. Population trends and management of the bank swallow

On the Sacramento River.

Garrison, Barry. 1991-2. Bank swallow nesting ecology and results of banding

efforts on the Sacramento River (annual reports).

Garrison, Barry. Biologist, California State Department of Fish and Game (personal

communication 2000).

Golden Gate National Recreation Area Advisory Commission power point presentation

on the bank swallow protection and habitat restoration project (January 18,

2000). National Park Service. Unpub.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area Advisory Commission meeting minutes (January

18, 2000).

Hatch, Daphne. Wildlife Biologist. National Park Service. (personal communication

1998-2000).

Hopkins, Alan. Golden Gate Audubon Society (personal communication, 1998-2000).

Howell, J. T., P. H. Raven, and P.R. Rubtzoff. 1958. A Flora of San Francisco,

California.

Wasmann Journal of Biology 16(1):1-157.

Laymon, Garrison, B. and Humphry, 1988. State of California Historic and Current

Status of the Bank Swallow in California.

Milestone, James F. 1996. Fort Funston's Bank Swallow and Flyway Management

Plan and Site Prescription (unpub.).

Morgan, D., and D. DahIsten. 1999. Effects of iceplant

(Carpobrotus edulis) removal and native plant restoration on dunedwelling

arthropods at Fort Funston, San Francisco, California, USA. (unpub. data).

Murphy, Dan. Golden Gate Audubon Society (personal communication, 1998-2000).

Percy, Mike. Roads and Trails Specialist. National Park Service (personal communication

1999-2000).

Petrilli, Mary, Interpretive Specialist, National Park Service (personal communication

1998-2000).

Pickart, A. J., and J. 0. Sawyer. 1998.

Ecology and Restoration of Northern California Coastal Dunes. Sacramento:

California Native Plant Society.

Powell, Jerry A. 1981. Endangered habitats for insects: California coastal sand

dunes.

Atala 6, no. 1-2: 41-55.

Prokop, Steve. Law Enforcement Ranger. National Park Service. (personal communication

2000).

Schlorff, Ron. Biologist, California State Department of Fish and Game (personal

communication 1999-2000).

Sherman, John. Law Enforcement Ranger, National Park Service (personal communication

1998-9).

State of California Department of Fish and Game. 1986. The status of the bank

swallow populations of the Sacramento River.

State of California Department of Fish and Game 1992. Recovery Plan, Bank Swallow

(Riparia riparia).

California Department of Fish and Game. 1995. Five Year Status Review: Bank

Swallow.

State Resources Agency. 1990. Annual report of the status of California state

listed threatened and endangered species. California Department of Fish and

Game, Sacramento, CA.

Summary of public safety incidents at Fort Funston, Golden Gate National Recreation

Area as of Jan. 23, 2000. National Park Service. Unpub data.

Summary of public safety incidents at Fort Funston, Golden Gate National Recreation

Area as of Aug. 24, 1999. National Park Service. Unpub data.

Summary of erosion and sand deposition along bluff-top fencing at Fort Funston,

Golden Gate National Recreation Area as of June

26, 2000. National Park Service. Unpub. data.

The Nature Conservancy and Association for Biodiversity Information,

2000.

Executive Summary, The Status of Biodiversity in the United States.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1991. Final Report: Evaluation of experimental

nesting habitat and selected aspects of bank swallow biology on the Sacramento

River, 1988-1990.

Wahrhaftig, C. and Lehre, A. K. 1974. Geologic and Hydrologic Study of the Golden

Gate National Recreation Area Summary (Prepared for the U.S. Department of the

Interior, National Park Service).

Bank

Swallow Project Statement, appendix to the Natural Resources Management Plan,

Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Feb. 16, 1999.

Compendium, Golden Gate National Recreation Area (signed by General Superintendent

and Field Solicitor). 1997. Golden Gate National Recreation Area. National Park

Service.

Draft Management Policies. 2000. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the

Interior.

Executive Order 13112 on Invasive Species signed February 3, 1999.

Fiscal Year 1999 Government Performance and Results Act, Annual Report, Golden

Gate National Recreation Area, National Park Service.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area Act of October 27, 1972, Pub. L. 92-589,

86 Stat. 1299, as amended, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 460bb

et seq.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area Approved General Management Plan. 1980.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area, National Park Service.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area Environmental Compliance (Project Review)

memorandum June 16, 1992 - Project Review Committee Recommendations for Approval

(Bank Swallow Protection Project).

Golden Gate National Recreation Area Environmental Compliance (Project Review)

memorandum February 1995 - Project Review Committee Recommendations for Approval

(Hillside Erosion Protection -Closure).

Golden Gate National Recreation Area Environmental Compliance (Project Review)

memorandum February 24, 1999 - Project Review Committee Recommendations for

Approval. (Bank Swallow Protection and Habitat Restoration Closure Project).

Golden Gate National Recreation Area Natural Resources Management Plan. 1999.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area, National Park Service.

National Park Service Management Policies. 1988. Department of Interior, National

Park Service.

Natural Resources Management Guidelines (NPS-77). 1991. Department of the Interior,

National Park Service.

Restoration Action Plan, Fort Funston Bank Swallow Habitat, 1992. Golden Gate

National Recreation Area.

Statement for Management, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, April 1992.

The Organic Act of 1916, as amended, codified at 16 U.S.C. § 1

et seq.

Park System Resource Protection Act, as amended, codified at 16 U.S.C. §

19jj

et seq.

National Park Service, Department of Interior, Regulations, 36 C.F.R. Parts

1-5, 7.

This GGNRA public document was converted to Web format by Fort Funston Forum, based on the original proposal available on paper at the listed locations. Fort Funston Forum added the (sic) notation to indicate possible errors in the original document, left unchanged as published. Please address any questions or comments to: editor@fortfunstonforum.com